I watched the drama series StartUp in a small window pulled to the right edge of my monitor, occupying less than a fifth of the screen area. Filling the rest of the space would be work: code, or talking about code, or complaining about talking about code. My attention would swing between the two rhythmically. A Martin Freeman monologue would fade into a music montage that let eyes move back to the code editor. A slow app rebuild would let me steal some glances at a gratuitous sex scene. Rhythm of the boredom. Sometimes the work would require too mutch focus and I would have to close the tab. Other times the show would capture my attention enough that I would give it the honor of full screen. The living pulse of a startup. The pure frenetic energy of getting jacked into whichever reality fits your mood. A four-dimensional experience. This was GenCoin.

Now, if you read things online the way I do, you probably skimmed over the ending of that paragraph. You got the vibe and sensed that nothing of substance was going to be added, just the same idea reinforced. That is an entirely fair approach to take. Your time is valuable. My time spent writing mild satire of silicon valley tropes is less valuable.

By the same token, you may not want to spend your time watching the direct-to-streaming show StartUp which ran from 2016 to 2018 for a grand total of thirty episodes. It was released on a Streaming as a Failed Service (SaaFS as we call it in the biz) that doesn’t matter. Its plot was built around news headlines of the time. It echoed news outlets perfectly, using the topics as bland slices of bread to wrap around human drama peanut butter & jelly. If that description doesn’t get your mouth watering, then I encourage you to save yourself thirty hours of carbohydrates and skip this one.

However.

The drama series hit Netflix in May of 2021, the same month I quit a tech job. Coincidence? Did StartUp give me the clarity I needed to see what was wrong with my work environment?

No.

I actually watched the NIXVM cult documentaries earlier in the year. Those are more representative of the working conditions of a startup than the show StartUp. One trope that is surprisingly absent from the show is the Charismatic Leader who steers everyone towards a common cause using reins of abuse and and flattery. StartUp seems to avoid this type of character as part of its thesis, instead focusing on a trio of flawed-but-not-too-flawed characters: Nick, the entrepreneur; Izzy, the entrepreneur; and Ronald, the entrepreneur. Okay, sure, they each have more backstory than that. But in the world of StartUp, the most important trait is a fetish for small businesses with big dreams. If the dream is big enough, it doesn’t even need a leader to form a cult.

What, then, is the dream at the heart of StartUp? What idea could unify an investor with daddy issues, a hacker with a destructive ego, and a drug dealer with a conscience? Why, only the most important topic of the twenty-teens:

Cryptocurrency.

That was a joke. I feel I have to clarify that, because you might be reading this in the far future, or you might really think crypto is a more important topic than climate change or the resurgence of white supremacy. Sadly, I have to inform you crypto was as vapid a subject as Beanie Babies while receiving as much attention as those other topics. At least those stuffed animals weren’t actively harmful. They didn’t contribute much to climate change, unlike the ongoing energy sink of etherium. I don’t think any rainbow bears helped neo-nazis raise money.

However, this essay is not about “crypto bad.” And there is no reason a TV show can’t use it as a subject. Breaking Bad doesn’t try to convince you that methamphetamine is good, actually. But it does portray the effects of the drug and its black market. The real fun of StartUp is how it fails to address any of the real problems with crypto. Instead it waves its hands at some technical jargon to condemn or redeem the characters as is convenient.

It is this silicon straw man that I am going to spend my time burning down. I am going to put too much effort into explaining how StartUp creates technology that is somehow sillier than reality. Then I will interrogate the characters to find out if they know it’s silly, and whether they are in on the joke. I hope my sacrifice can help you enjoy this show, whether or not you choose to suffer through watching it yourself.

The Pitch

The first episode of StartUp introduces the technology that will unite its three main characters: GenCoin. It is the brainchild of Izzy Morales, our resident computer wizard with an ambiguously edgy past. We find her struggling to keep server racks running in her parent’s garage while she hops between meetings with potential investors. She pitches her creation to the suits and to us, the audience, simultaneously:

Did you know that in Saudi Arabia a woman can’t open her own bank account? In Indonesia, the instability of the rupee makes it impossible to maintain a business. But what if, what if there was a currency they all had access to? A currency they could call their own. A currency with no borders, free of government decree, with no threat of confiscation. Did you know 50% of the world population, that’s three and a half billion people, don’t have access to a bank account, but by 2020, almost all of them will have a cell phone. That’s power. That’s GenCoin.

Before picking apart the details of what Izzy has created, let’s first assume that everything she proposes here is correct. These problems exist as she describes them, and GenCoin can do something to fix them. What stories does this premise set up? What kinds of conflicts do we expect Izzy to face as she progresses towards this goal?

We might expect to follow the story of a woman in Saudi Arabia struggling for independence who uses GenCoin to change her circumstances. We could follow a cast of characters around the globe, in the style of Sense8, each of whom become users and contributors to the growth and power of GenCoin. If that is too ambitious, perhaps our characters have immigrated to Miami (the city where we have chosen to set our TV show already) after struggling with these social and financial problems in their home countries.

But no, this is not a story that StartUp is going to tell.

Ok, well, that monologue says a lot about reducing government control. Will this be the story of how the global economy shifts due to one woman’s creation? She could become a political prisoner, an icon for anti-government groups, and either a pro- or anti-capitalist activist depending on how the dominoes fall. The end of the first season could take us into speculative fiction territory. With Miami as the hotbed for revolution, maybe Florida secedes into its own country allied with Cuba!

But no, StartUp does not want to speculate. At least, not in the fun way. It’s only willing to speculate on the popularity of cellphones. Less than two-thirds of the world’s population had cellphones in 2020, by the way.

Perhaps the writers were aware of how inauthentic this pitch is. While Izzy gets a few lines of exposition of how her family struggled with money, it can’t away from the fact that she went to Stanford and has her parents’ garage to store her computers in when the going gets tough. She never claims to have first-hand experience of the problems she wants to solve, or any specific examples of how the existence of GenCoin would change her life.

Instead, StartUp turns to Ronald Dacey for that authentic “underbanked” flavor, though the effect is somewhat undercut when his primary use for banking is to launder drug money. Ronald is a Haitian immigrant who is heavily scripted to have both the hardest hardships and purest conscience. In the pilot episode he spares the life of a rival gang member, to the disdain of his subordinates. StartUp screams at us that if ever there was a man who deserves to break out of poverty, it’s Ronald Dacey.

And yet the reason Ronald’s investment plans are foiled is not government control or an unstable currency. No, a single corrupt banker runs off with his money. This banker was the father of our other main character, Nick Talman, who is clearly not underbanked. That means we are zero-for-three on characters who’s problems would be solved if Izzy’s pitch were to succeed.

Without a personal motivation, is it possible that our characters are driven by altruism? Did Izzy let a “molly-popping Key Rat cum inside [her] for a year” because she wants an unspecified Saudi woman to open a bank account? That is not the story that StartUp tells us. Instead, it shows us a developer who is obsessed with competition. She is devoted to the technology, and changing the world is just the validation of her genius. The script pounds this idea into our heads: Izzy spends more time explaining how good her code is than what it actually does. She says “it works” so often that it becomes suspicious – fortunately some outside coders show up to tell us how awesome it really is.

This is how StartUp lets us know that Izzy’s pitch is hollow. Her focus is the technology, which invites us to focus on it as well. This is where the questions really get fun.

Is It Like PayPal?

The pilot episode also introduces us to this question that will become a refrain throughout the first season. The repetition of the PayPal question is intended to be a joke: here we are explaining The Next Big Thing and these people can’t stop thinking about a website from the dot-com era. The implication is that the difference is so stark that if you can’t see it you just don’t get it. This suggestion of ignorance is further reinforced with references to a “complex algorithm” that took years to develop. But the repetition works against itself as we build a resistance to the cliche. How isn’t it like PayPal?

Perhaps PayPal does not use a complex algorithm. That is a hard argument to make without additional details – clearly a website that works in hundreds of countries and moves money between major banks and credit cards achieves some level of complexity. So the details of GenCoin’s algorithm must be important. Here is an exhaustive list of everything we learn about the algorithm in the first season:

It predicts, it adjusts, and adapts to foreign markets and political shifts in order to remain stable.

Oh, that was quick. Even Bitcoin magazine hoped the show would elaborate, but there is no explanation of these features after Izzy’s pitch in the first episode.

Absent any specifics, we are left to infer that GenCoin adapts in a way that an online payment system does not. Without digging too much into the question of what it means for a currency to have value, there are two different explanations for what this algorithm does:

- It predicts how international currencies will change in value and enforces exchange rates whenever a user wants to convert between GenCoin and another currency.

- It predicts the demand for GenCoin itself and adjusts the currency in circulation to counter these changes, essentially printing or shredding digital reserves.

Option #2 seems very cool. Sadly, that means it can’t possibly be the option that StartUp intended. Being able to predict the future like this would enter the realm of science fiction. How far into the future can it predict? Does Izzy already know that GenCoin succeeds at the end of season one? Or, if the algorithm is more speculative, it must know how to avoid overcompensating and getting stuck in a loop of hyperinflation/deflation. If Izzy knows how to solve these problems, then maybe she should be consulting with the Federal Reserve or the IMF instead of starting some little cryptocurrency. No, these ideas are far too interesting for StartUp – let’s leave the science fiction to Devs.

Option #1 is more reasonable, assuming that the algorithm is just speculating (as predicting would put us back into science fiction). With this system, GenCoin would need to include a marketplace for purchasing the currency at the predicted rates. For example, a website which accepts bank transfers in exchange for a GenCoin balance that is equal to the source currency’s value. Perhaps there would be a FAQ on the website that explains the currency exchange rates. Maybe the payment platform would be integrated with an online marketplace, like PayPal and eBay in 2002. Hey, the show actually does that in season two!

It looks like we’re on the right path, and that path leads us straight back to PayPal. Would Izzy’s algorithm be better at setting exchange rates than the system PayPal uses? Payment platforms use exchange rates set by major banks, which rely on data from the global foreign exchange markets. These markets handle trillions of dollars per day which is a pretty good sampling of how much the world is willing to spend on various currencies. If GenCoin is really able to predict changes before these rates adjust, Izzy would probably be better off getting into the currency speculation game.

The lines that separate Gencoin from PayPal blur into invisibility as we inspect how they operate. The only distinction that remains is the motivation behind them, right?. Izzy wants “a currency with no borders” even though she is an American entrepreneur. Perhaps she was inspired by a certain libertarian thought leader:

The founding vision of PayPal centered on the creation of a new world currency, free from all government control and dilution — the end of monetary sovereignty, as it were.

Peter Thiel, 2009

At Least It’s Not Bitcoin

The PayPal comparison shows how GenCoin falls apart under the slightest interrogation. It still has one trick up its sleeve, though: cryptocurrency camouflage. By inviting comparisons to Bitcoin, StartUp hides one lie behind another.

It is customary at this point in any discussion of crypto to give a summary of what blockchain is and use the phrase “hard math problems” a few times. Fortunately, we don’t need to do that. You are welcome.

We don’t need to understand this technology because StartUp doesn’t mention it. Perhaps it was too obscure for 2016, before the “blockchain” keyword had reached maximum titillation. In any case, here is the entire explanation of how Bitcoin is inferior to GenCoin:

Its code is open source… Which makes it susceptible to third-party interference and, ultimately, corruption.

Unfortunately, this means we need to be on the same page about what “open source” means, a much simpler idea than “blockchain” with a much more complicated history.

First, what is the source? For a program to run on a computer, it needs to be in a format that the hardware can use. Imagine this is like a recipe in a chef’s head: they know how to cook the dish, but we can’t crack open their brain to understand what they’re doing (or at least it would be very difficult and rude). When a company sells closed-source software, it is like they are selling trained chefs who can make recipes for us. These chefs refuse to explain what they are doing, and they reject any modifications that are suggested.

When a company sells open-source software, it’s like the chef comes along with the recipe in a written, step-by-step format which we could learn ourselves. If we don’t like the original chef, we can train our own with some modifications. Then kick the original chef to the curb. Too much onion, dude.

This chef analogy is perfect, so don’t be surprised when your brain melts like fondue when you try to understand the “corruption” explanation above.

A cryptocurrency is just a program that runs on a bunch of computers connected over the internet. When we create a modified version of that program, it does not modify any of the other computers that are running the original – what happens in our kitchen stays in our kitchen. We could modify our program to say that we have a hundred billion Bitcoin in our wallet, but we would only be deluding ourselves. When we try to exchange this currency with the rest of the network, they are going to use the consensus of what our balance is. So our modified version of the program will, at best, function exactly the same as the original. At worst, our program will speak complete nonsense and the rest of the network will simply ignore it. Like a chef drunk dialing their friends asking for more onions.

Astute readers (or owners of chain restaurants) may be wondering what happens if we train enough of our onion-obsessed chefs and send them out into the kitchens of the world. Can we create our own consensus that bends to our will? Congratulations, we just invented Bitcoin forks: spin-off currencies that vie for popularity. The limiting factor is not whether we can create an alternative currency. That is easy. The problem is convincing other people to use it and, therefore, give it value. And it’s going to be an uphill battle too if our spin-off includes some nonsense like giving us unlimited onions currency.

Although, if we hid the malicious changes it would be easier to recruit users. If we, say, closed off our source code it would be much harder to identify how our program is different from Bitcoin. Users would have to trust us, the creators. So we could lay low, never abusing our changes, until the currency gained enough value that we could start skimming off the top. Users would have to analyze the behavior of the entire network to find the “mistake” and even then we might be able to convince them it was just part of the “complex algorithm” working as intended.

While searching for a scheme to create “third-party interference” we ended up creating first-party corruption using the exact scheme that GenCoin proposes. The idea of closed-source software being less susceptible to corruption is laughable. And StartUp is not in on the joke. The reality is that closed-source software is more likely to be a vector for intentional abuse by the company, or just classic malware. There is a reason that users were concerned about giving a video game ultimate control of their PC while developers are annoyed by tools that are too cautious when installing open-source software.

If our chef won’t listen to us, we have to let them to poison us. With onions.

Intentional Abuse

StartUp is not self-aware.

I was going to pose that as a question, but after exploring the contradictions in its central pitch I can’t find any evidence that the writers planned on exploring them. Instead, the writers amplify the show’s incompetence with a technical pivot in the second season that becomes incomprehensible by the third.

As mentioned earlier, GenCoin eventually becomes a payment system for a digital marketplace, just like PayPal. The eBay in this story is called “Araknet” which, yes, is hard to say and which, yes, will be said a dozen times per episode. In addition to being a marketplace, Araknet also refers to the “dark web” that is necessary to access the site. The distinction is awkward and is never clarified by the show. Imagine if Amazon referred to both the online store and the platform that hosts the website. Or if Google owned both a store and the internet service used to connect to the store. Maybe it’s not that strange after all.

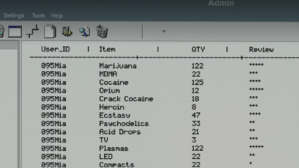

The only thing StartUp needs us to know about Araknet is that we can do crimes with it. Ronald’s son suggests selling drugs online to grow their business. Izzy, of course, can build it, and Nick can have sex with someone. Like GenCoin, Araknet is free from government oversight and is therefore a tool of democracy. It will provide a market for the under-marketed – mainly drug dealers.

There is no discussion of the technology that makes Araknet possible. There isn’t even an elevator pitch that I can quote and then nitpick. Instead, we have to infer what Araknet offers based on its real-world predecessors: Tor, the original dark web, and Silk Road, the online black market.

The comparison to Silk Road is easy: there is no difference, except that Araknet runs on the fictional network and uses a fictional currency. Our fictional characters are clearly aware of this site, and so would have to know that Silk Road lasted about three years before its founder was sentenced to life in prison. For some reason, this does not prevent our characters from going on television and talking about how cool and popular Araknet is. They appear to operate like any other software company, except with a few more visits from the Russian mob. Their dark web appears to be so powerful that its protections burst out of the internet and manifest in the rest of reality.

StartUp uses some TV magic to convince us the characters have plausible deniability. In the few brief screenshots of the black market we see, the website does not broadcast the Aaraknet affiliation, instead using the name “Silence Quest.” However, the conclusion of the second season hinges on the idea that Araknet controls which currencies can be used in this marketplace (yep, we’re back to currency). For this to be possible, Araknet must have such deep control of how sites operate that their smokescreen would fall apart under the slightest scrutiny. The name of the site is an aesthetic change that tries to prevent the viewer from wondering why our main characters aren’t arrested in the third episode of the season.

The other technology that Izzy clones is Tor, a piece of software that is alive and well today because it is not exclusively intended for crime. “The Onion Router” allows a site and its users to stay anonymous by bouncing traffic around the network. Imagine a chef who sends some ingredients to… Just kidding, we don’t need a metaphor here. We only need to know that Tor works in the real world, and when Izzy explains Araknet she just summarizes Tor’s Wikipedia page. And, though they seem to be identical, the real-world net provides two essential security features which StartUp completely fumbles.

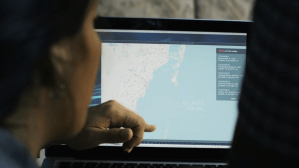

Izzy kindly explains the first feature to Ronald, his son, and the audience by pointing at blinking dots on a map of Miami. She gives an example of how traffic from Liberty City gets passed through computers in Miami Beach, Coral Gables, Overtown, and finally Homestead.

We have to assume that this is just a hypothetical route; if this were an actual transaction she was able to trace then her network has already violated the anonymity of its users. However, even if we assume the technology is working as promised, there are two big problems with this network: it’s only in Miami, and it’s only used by drug dealers.

Imagine we are law enforcement investigating the Miami drug trade. One day we hear about Araknet – an informant mentions it, a user is caught with their purchase, or a flash drive is confiscated from a dealer. Remember, this network is trying to grow via word of mouth. If these folks were using Tor we would have a real problem: that network covers the entire globe and is full of traffic that has nothing to do with the Miami drug trade. Fortunately, we have a network that is entirely in our jurisdiction and where every node has a good chance of pointing us to another potential informant. Heck, did Izzy set up this honey pot just for us?

StartUp blazes past this obvious opening for law enforcement, distracting us with sexy, murderous Martin Freeman. It waits until the third season to have the feds come and knock over an even more important security feature: encryption.

By the time season three came out in 2018, digital privacy had eclipsed cryptocurrency in tech news headlines. Some of the concern came out of the same libertarian hyper-capitalist milieu as Bitcoin, but much of it had a very practical message for the average user: tech companies can snoop on our private messages. Applications like Signal gained some traction for their promise of end-to-end encryption which ensures messages can’t be read by the company standing in the middle. This was also the year that Google Chrome started flagging unencrypted sites as insecure. However, the technology that enabled this encryption had been around since the year 2000. Tor users were aware of the necessity of these security measures back in 2007. By 2013, criminals like the creator of Silk Road were not getting caught due to a lack of encryption.

If our characters did their homework, they would know how the guy behind Silk Road was caught. It wasn’t because the FBI found a way to track his activity on Tor. No, he slipped up by posting to public forums using his personal email. The FBI used a few normal subpoenas from there to find his location on the not-so-dark web.

Ronald, co-CEO of a company that makes privacy software, does not know this history. So, when the law finally comes to investigate the network, he is left defenseless. The NSA asks for records of communication between terrorist organizations – records that should not exist. If their dark web and its services lived up to Izzy’s galaxy-brain standards, Araknet should be entirely incapable of exposing private messages between users. At most they would have encrypted blobs of nonsense, and exposing those would require the kind of work that Apple fought the FBI over in 2016. But when Ronald asks the company’s cybersecurity expert to gather this information, there is no discussion of this. She creates a database of criminal activity on the network in a matter of days.

StartUp attempts to distract us from this huge hole in Araknet’s security by presenting Ronald’s moral dilemma as the focus of the season. He is shocked by the revelation that hitmen and terrorists are doing business on his network that was built for his friendly, neighborhood drug dealers. Bizarrely, he is the character who wants to cooperate with law enforcement. Does this mean he is willing to betray his former gang? Nope, the first thing he does is delete all of their records. This abuse of power is portrayed as a noble choice.

Meanwhile, Izzy is blackmailed into distributing malware through an Araknet update. That’s not even related to the encryption problem. I just thought I should mention it.

The collapse of Araknet’s security is StartUp’s last chance at self-reflection. This problem undermines any of the show’s statements on free speech, morality, and privacy. Araknet’s most basic technology – the foundation for everything else they could possibly build – is a sham. The company can’t even meet the standards of Tor, an open-source network that had been running off volunteer support since 2002. This could spark an interesting discussion of the “embrace, extend, extinguish” principle and how capitalist interests can lead to less innovation. We could finally get the reveal of how closed-source was more prone to corruption all along.

But this is not a story that StartUp tells.

Dump The Body

In the end, Izzy’s supposed genius contributes nothing to society that wasn’t already available for free and with less corruption. None of the main characters confront the fact their cryptocurrency never brought bank accounts to Saudi Arabia. They never admit that the core of their company was void, corrupt, and useless. Their story beats are all played on the well-worn drums of money, murder, and megolomania.

The final scene of StartUp makes use of the show’s most vivid motif: feeding a dead body to alligators. The central conflict of the final season is wrapped up by shooting a person. If StartUp does have a message, perhaps it is a metaphor for technology in TV: every idea is murdered and its carcass is consumed by hungry beasts. Or perhaps the show is a body, the viewers are murderers, and Netflix is a swamp. I only hope that all scams like GenCoin and Araknet eventually suffer the same fate.